[시드니와 함께하는 세계 속 붓다의 딸, 6탄]

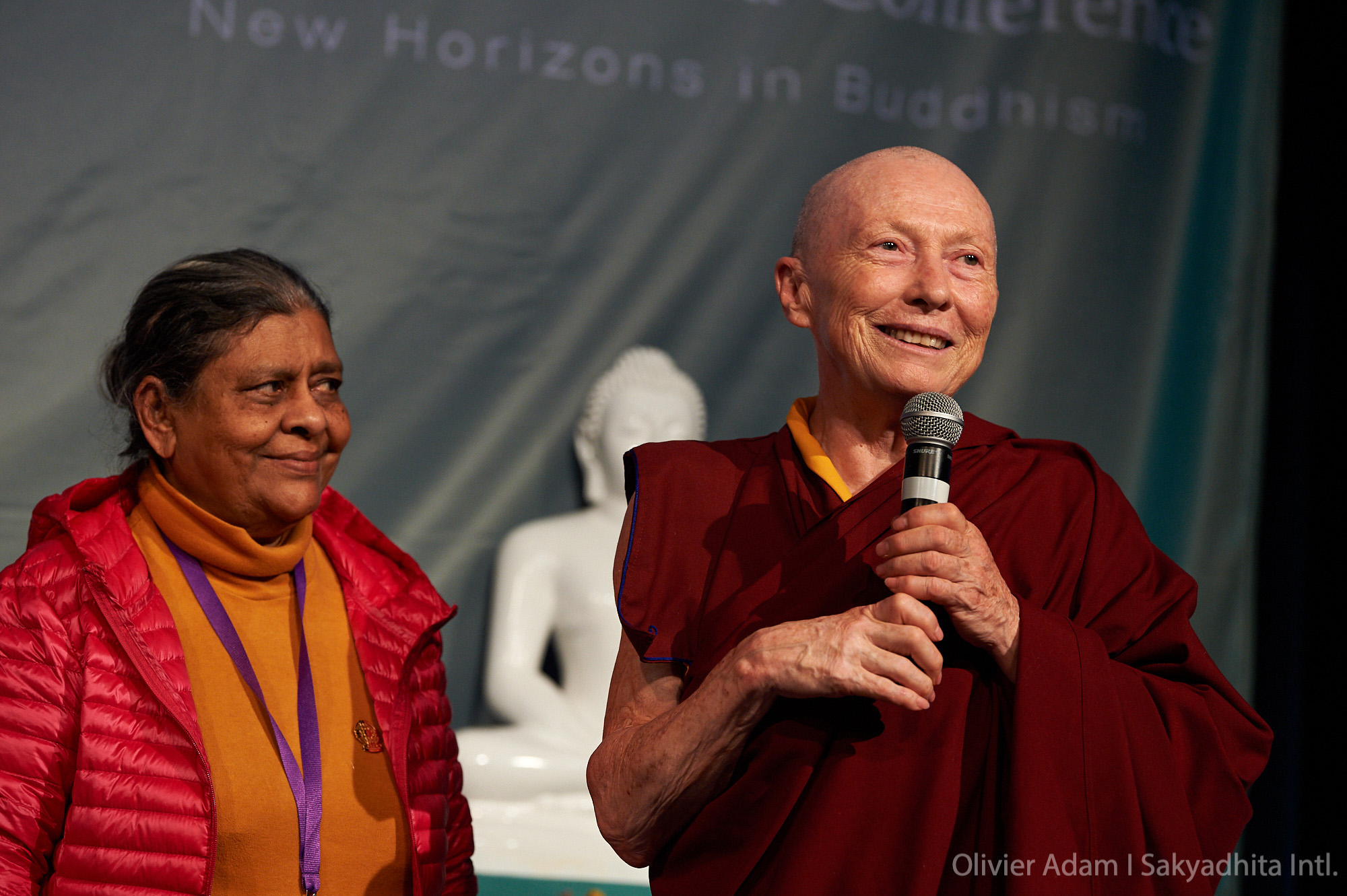

인터뷰: 샤카디타 인터네셔널 카르마 렉셰 쏘모스님

Interview with Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo

쏘모스님은 샤카디타 세계불교여성연합의 창립멤버이자 그동안 대회를 꾸려온 주역이다. 샤카디타 하와이를 이끌면서 인도와 방글라데시에 잠양재단을 운영하고 계신다. 지난 2017년의 홍콩대회를 마지막으로 대회 준비위원에서 한 발짝 물러난 소감을 물어보았다.

*기자: 시드니 톰슨, *인터뷰: 신미아, *번역: 신미아

신미아 Mia:

![]() 안녕하세요, 스님. 먼저 한국의 독자들을 위해 스님 소개를 부탁드립니다.

안녕하세요, 스님. 먼저 한국의 독자들을 위해 스님 소개를 부탁드립니다.

Hello. For our readers in Korea, could you please give us a brief background introduction of yourself?

카르마 렉셰 쏘모스님 Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo:

![]()

안녕하세요. 저는 미국인이며, 성은 젠(Zenn)입니다. 독일식 이름인데, 아마도 오래 전에 이민국에서 철자를 잘못 쓴 것 같아요. 여하튼 이 성 때문에 선불교 신자냐고 놀림을 많이 받았지요. 그래서 도대체 선불교가 뭔지 찾아보게 됐어요. 불교 관련 서적을 두 권 구해서 읽어보았는데, 그 철학에 깊이 공감하게 되었습니다. 그때부터 불교에 대한 책을 계속 읽었어요. 스승님을 찾아보려고도 했습니다. 하지만 그때가 1950년대였으므로 북미 대륙에서 불교에 대해 아는 사람은 거의 없었습니다. 어쩔 수 없이 저 스스로 길을 찾아야 했고, 결국 아시아로 갔습니다. 그 후 아시아에서 이십 년 정도 살았는데, 대략 십오 년 동안 인도 다람살라에서 공부했어요. 조금씩 계속 불교를 배우려고 노력했지요.

1987년에는 샤카디타 세계불교여성협회(이하 “샤카디타”) 일을 시작했습니다. 잠양재단도 이 무렵 설립했지요. 이 재단의 목적은 개발도상국에 사는 여성불자들에게 교육 받을 수 있는 기회를 제공하는 것입니다. 주로 인도와 방글라데시에서 사업을 하고 있고, 네팔이나 몽골 등에서도 활동을 하고 있습니다. 그러다가 1989년에는 독사에게 물리는 바람에 제 삶이 끝날 뻔 했습니다. 다행히도 살아 남긴 했는데, 몸이 너무 약해져서 인도로 돌아가지 못하고 미국에 있는 대학으로 갔지요. 그 곳에서 철학 박사 학위를 마치고, 천주교 성자의 이름을 딴 샌디에고 대학이 저를 고용해주었습니다. 그 곳에서 지금까지 이십 년 넘게 불교를 가르치고 있어요.

그리고, 2년마다 아시아 여러 나라에서 샤카디타 세계여성불자대회(이하 “샤카디타 대회”)를 개최하였습니다. 회의가 끝나면 여성불자가 여성불자에 대해 쓴 글과 논의내용들을 모아 출판물을 발간합니다. 일부 출판물은 학술서적으로, 일부 자료는 사람들이 알기 쉽게 펴냅니다. 모두 샤카디타 누리집에 올라와 있습니다. 샤카디타는 일 년에 한 번씩 소식지도 펴냅니다. 참 대단한 일이지요!

I’m American and I was born into a Family with the last name Zenn. It’s a German name, which was probably misspelled at immigration, but, because of this name, I was teased for being a Zen Buddhist. So, then I had to find out what Zen Buddhism is, and I went and found two books on Buddhism, and, when I read them, I resonated with the philosophy very closely. From that time on, I continued to read about Buddhism, and I tried to find teachers. However, this was very early on, in the 1950s, so there was very little about Buddhism in North America. Therefore, I had to find my [own] way and eventually went to Asia. I lived in Asia for about twenty years and studied in Dharamsala for about fifteen years. I gradually tried to learn more and more about Buddhism.

In 1987, we started Sakyadhita, and I also started Jamyang Foundation, which is to provide educational opportunities for Buddhist women in developing countries. We work especially in India and Bangladesh, with outreach programs in Nepal, Mongolia, and so on. Then, in 1989, I got bitten by a poisonous snake, a viper, and that was almost the end of my story. Luckily, I survived, but since I was too sick to go back to India, then I went back to university and wound up with a degree in philosophy and was hired by the Catholics to teach Buddhism. So, there I am at the University of San Diego, and I have been teaching there for about twenty years now.

Every two years, I’ve been organizing the Sakyadhita conferences in different countries around Asia and then compiling the talks into publications, anthologies, on Buddhist women by and about Buddhist women. Some have been published as academic works and some have just been publicly accessible – we’ve been putting them up on the Sakyadhita website. We also publish some in the Sakyadhita newsletter once a year and so on. It’s been great!

신미아:

![]() 스님께서 잠깐 말씀하셨는데, 기독교가 압도적인 미국에서 어떻게 불교와 인연이 닿으셨는지 좀 더 설명해주시겠어요?

스님께서 잠깐 말씀하셨는데, 기독교가 압도적인 미국에서 어떻게 불교와 인연이 닿으셨는지 좀 더 설명해주시겠어요?

As a person from the United States, which is predominantly a Christian country, how did you encounter Buddhism?

카르마 렉셰 쏘모스님:

![]()

예, 제가 조금 전 말씀드린 그 불교 관련 책들을 읽고 나서 어머니께 “엄마, 저는 불교 신자예요!” 하고 말씀드렸답니다. 어머니는 깜짝 놀라셨지요. 어머니의 종교에서 보자면 그건 지옥불에서 영원히 타게 된다는 뜻이니까요. 그래서 걱정을 무척이나 많이 하셨어요. 하지만 결국 어머니께서도 받아들이게 되셨습니다. 원래 어머니는 제가 기독교 선교사가 되기를 바라셨지요. 저는 어머니께 종종 “엄마, 저는 미국에서 불교 선교사가 될래요.” 하고 말씀드렸어요.

Well, after I read those books [on Buddhism], then I told my mother, “I’m a Buddhist.” She was shocked, horrified, because, in her tradition, that meant I was going to roast in hell for eternity. So, she was very worried. However, eventually she started to accept it. She initially wanted me to be a Christian missionary and I used to reply, “Mom, I’ll be a Buddhist missionary to America.”

신미아:

![]() 스님께서 재가수행자가 아니라 출가를 선택하신 이유가 있으신지요?

스님께서 재가수행자가 아니라 출가를 선택하신 이유가 있으신지요?

What motivated you to become a monk rather than a layperson Buddhist?

카르마 렉셰 쏘모스님:

![]()

저는 별별 일들을 다 해봤어요. 음악가도 되어보고 파도타기선수도 해봤어요. 요가를 가르치기도 하고 번역가가 되기도 했지요. 제가 꿈꾸던 일들은 거의 다 해봤습니다. 하지만 불교 수행만큼 저를 궁극적으로 만족시킨 것은 없었어요. 제 마음은 온통 불교 수행에 가 있었습니다. 그래서 출가하자고 생각했지요. 처음에는 비구스님이 되려고 했는데, 여자니까 비구스님은 될 수가 없으니 비구니스님이 되기로 했지요. 이렇게 큰 결심을 한 다음에도 실제 비구니가 되기까지는 시간이 꽤 걸렸습니다. 미국에 살다 보면 여기 저기 정신을 빼앗기게 됩니다. 게다가 그 당시에는 절도 없었고, 스승님도 관련 서적도 거의 없었어요. 그러다보니 시간이 좀 걸렸지요. 그러다가 1977년에 운좋게도 비구니가 될 수 있었어요. 이미 서른 두 살이 된 저는 제 삶을 온전히 불교 수행과 공부에 바치고 싶었죠. 더 이상 여기 저기 끌려다니며 삶을 소진하고 싶지 않았습니다. 진심으로 불교 수행에 전념하고 싶었어요.

Well, I did just about everything else – I was a musician, I was a surfer, I was a yoga teacher, a translator; I sort of lived out my dreams, but I found that nothing really satisfied my ultimately except Buddhist practice. My heart was totally into Buddhist practice. I had this idea of becoming a nun – first, I wanted to become a monk, then I realized I’m women, so I cannot be a monk. So, then, I decided I would become a nun. It took me a long time, though, between when I made this aspiration to when I became a nun because life in the States is very different; it pulls you in all different directions. There were no monasteries, there were very few teachers and very few books at that time, so it took me a while to become a nun. However, finally, I was very fortunate in 1977. I was already 32 years old, but then I became a nun because I wanted to dedicate my whole life to Buddhist practice and studies instead of getting torn in so many different directions. I really wanted to focus on Buddhist practice because that’s where my heart was.

신미아:

![]() 스님께서는 샤카디타 창립을 주도하셨는데요, 그동안 회장으로 오랫동안 봉사하시다가 얼마 전 은퇴하신 것으로 알고 있습니다. 소회가 어떠신지요?

스님께서는 샤카디타 창립을 주도하셨는데요, 그동안 회장으로 오랫동안 봉사하시다가 얼마 전 은퇴하신 것으로 알고 있습니다. 소회가 어떠신지요?

You led the establishment of Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women, and recently retired after serving as chairperson. Please tell us how you feel about that.

카르마 렉셰 쏘모스님:

![]()

아, 제가 샤카디타에서 은퇴했다는 것은 사실 잘못 알려진 겁니다. 샤카디타 대회 주최자 노릇에서 물러난 거지요. 그동안 저는 사람들에게 누누이 2017년 홍콩 대회가 끝나면 그 역할은 그만하겠다고 얘기했어요. 샤카디타 대회를 개최하려면 거의 일년 반 동안 꼬박 준비해야 합니다. 완전히 자원봉사이구요. 저는 한 번도 어떤 보상이나, 심지어 제 여행경비도 받은 적이 없습니다. 보통 회의를 개최하기 전에 개최국에 네 다섯 번, 또는 그 이상도 가봐야 합니다. 회의가 끝나면 자료집을 편집하는데, 그 일도 시간과 힘을 많이 쏟아야 합니다.

삼십 년 동안 이 일을 해오다 보니, 이제는 새로운 세대가 이 일을 끌어가야 한다는 생각이 들었어요. 그렇지 않으면 젊은 세대가 일을 배울 기회가 없을 테니까요. 물론 대회를 개최하는 것은 큰 즐거움입니다. 어려운 일이기도 하구요. 샤카디타가 다양한 문화권과 일하는 방식은 다른 단체들과 좀 다릅니다. 특히 자원봉사단체들 하고요.

우리는 여성도 이런 일을 할 수 있다는 것을 꼭 보여주고 싶습니다. 이미 많은 여성들이 이런 형태의 문화교류를 이끌어오고 있습니다. 개회식때 나라별로 돌아가면서 서로 다른 언어로 기도를 드리는 것은 샤카디타가 처음 시작한 것입니다. 이제는 다른 불교 행사에서도 여러 가지 언어로 경전을 독송하며 개회하는 것이 일반화됐지요. 또 샤카디타 대회는 토론만 하는 것이 아니라, 명상과 워크숍, 문화행사를 함께 결합시켰습니다. 역시 샤카디타만의 특별한 점입니다. 이렇게 샤카디타는 처음부터 새로운 길을 걸었고, 이것이 점차 국제적인 움직임으로 확산되었습니다. 무수히 많은 나라에서 온 여성들이 언어도 다르고 배경도 다르지만 다같이 일하고 있다는 점은 자랑할 만 합니다. 처음부터 우리는 재가여성들과 출가여성수행자 간의 연대를 구축하려고 했고, 이 원칙에 따라 일해왔습니다. 이것 역시 특별한 점이지요.

저는 이제 더 이상 샤카디타 대회를 준비하지 않기 때문에, 좀 여유가 생겼습니다. 사실 제가 하던 홍보나 출판 같은 다른 일들도 좀 넘기고 싶어요. 젊은 세대가 맡아주기를 바랍니다. 반면에 잠양 재단 일은 아직도 제가 열심히 하고 있습니다. 우리는 여성 교육의 중요성을 계속 강조하고, 또 지원해야 합니다. 교육 없이는 여성들이 동등해질 수 없기 때문이지요. 교육을 받으면 자신감이 생깁니다. “그래, 할 수 있어.”하는 마음요. 그러면 다른 사람에게 의존하지 않고, 스스로 자유롭게 새로운 길을 만들어 갈 수 있습니다.

Actually, it’s a misconception that I retired from Sakyadhita. I don’t know how this rumor got started. What I did was I stepped down as the organizer of the Sakyadhita conferences in Hong Kong. I told everyone one year in advance that I would be stepping down after the Hong Kong conference. Why? Well, because each conference took a year and a half of fulltime service. It’s completely voluntary. I never received any compensation or even any contribution toward my travel expenses. It was all as a volunteer. For each conference, I usually needed to go to that country three, four, five times, sometimes more, in order to set everything up. Then, compiling the books afterwards also took so much time and energy.

So, I thought that after 30 years of this, it was time for a new generation to have the opportunity to become leaders. If our generation continues to lead the organizations, then the younger generations won’t have a chance to learn how to do it. It’s such a great joy and, of course, it’s a challenge as well. What Sakyadhita does in working across cultures is unlike most organizations, especially volunteer organizations.

We really want to show that women can do this; women have actually been leaders in this kind of cross-cultural exchange. The tradition of starting the conferences with prayers of the different traditions was started by Sakyadhita. Now, it’s become common for Buddhist conferences to start with reciting sutras in different languages. It was women who started this; and then, the idea of integrating meditation and workshops and cultural performances into the conference, instead of just talking words, and words, words, this is really special about Sakyadhita. In these ways, Sakyadhita has forged a new path from the beginning and it has grown into an international movement. I think that we can be very proud that women from so many different countries, speaking so many different languages, and from so many different backgrounds can all work together. Our original decision to forge an alliance of laywomen and nuns and those that are neither lay nor ordain has been our way of working since the beginning, so this is something very special.

Now that I’m stepping down from organizing the conferences, I have more time to do some of the other work. I would like to pass on some of the other duties as well such as communication, social media, publications and so forth. Some of the other work that I have also been doing I hope the younger generation will also take up. Meanwhile, Jamyang Foundation, our educational foundation, is something I’m still dedicated to because without education there’s no equal playing field for women. We have to continually encourage and support women to become educated because with education comes confidence, that “yeah, we can do this” attitude. We don’t have to rely on others for everything, we can do it ourselves. Then, we’re free to forge new directions.

신미아:

![]() 잠양재단은 스님께서 설립하신 단체라고 말씀하셨는데요, 좀 더 소개해주시겠어요?

잠양재단은 스님께서 설립하신 단체라고 말씀하셨는데요, 좀 더 소개해주시겠어요?

For the Buddhist community in Korea, could you please introduce the Jamyang Foundation, another organization that you founded?

카르마 렉셰 쏘모스님:

![]()

제가 인도 다람살라에서 공부하고 있을 때였습니다. 저는 많은 티베트 여성 불자들이 읽고 쓰지 못한다는 것을 알게 되었습니다. 저는 이 분들이 글을 읽을 수 있도록 꼭 도와야 한다는 생각이 들었어요. 처음에는 이 분들도 별로 자신이 없었습니다. 여성들은 교육에 관심이 없고, “옴 마니 반메 훔”만 외울 수 있으면 충분하다는 얘기를 늘 들었기 때문이지요. 물론 기도문도 외워야 합니다. 하지만 이 분들이 글을 읽을 수 없다는 사실에 대해 미국인으로서 저는 “이 분들도 기회를 가져야 한다.”는 생각을 했습니다.

그래서 문해교육사업을 시작했지요. 그 다음에는 티베트어를 가르치고, 철학, 영어 등 다른 과목들도 가르쳤습니다. 이렇게 해서 1986년에서 1987년 즈음에 잠양재단이 시작되었습니다. 샤카디타와 거의 같은 무렵입니다. 좀 더 인도 현지에 특화된 사업이라고 할 수 있지요. 엄청난 수요가 있었거든요. 나중에는 방글라데시까지 아우르게 되었습니다. 잠양재단이 하는 교육 과정에 재가 여성들도 참여할 수는 있었지만, 본질적으로는 여성 출가수행자들을 위한 프로그램이었습니다. 티베트 언어를 사용해 불교를 가르치는 거지요. 히말라야 지역 사람들은 불심이 깊어지면 보통 출가를 하려고 합니다. 방글라데시 학교에서는 주로 어린 소녀들이 공부합니다. 이 소녀들은 방글라데시와 미얀마 국경 지대 마을에 살고 있습니다. 이 곳에 불교도들이 많이 사는 데, 방글라데시 전체 인구의 약 1% 정도를 차지합니다. 방글라데시 학교에서 벌인 소녀교육사업은 큰 성과가 있었습니다. 이 소녀들은 다른 곳에서는 전혀 교육을 받을 수 없었고, 또 납치와 인신매매를 당할 우려도 컸습니다. 소녀들이 교육을 받으면 좀 더 자신감을 갖고 경제적 기회도 생깁니다. 아주 다행이지요.

When I was a student in Dharamsala, I noticed that many of the women in the Tibetan tradition could not read or write, especially those coming from Tibet. I thought we really should do something to help them read. At first, they didn’t have confidence to read because they had been told that women are not interested in education and it’s enough for them to say om mani padme hum. Of course, they would memorize their prayers, but the fact that they could not read the texts, as an American woman I thought “they should have the opportunity.”

So, we started with a literacy program, then we expanded to teach Tibetan language, then philosophy, and then eventually English and other subjects. That’s how Jamyang Foundation began in 1986-87, around the same time as Sakyadhita. However, this was a more localized project, especially in India where the need is really great. Later, we expanded to Bangladesh. In India, while laywomen could participate, the projects were mostly for nuns. It was a Tibetan medium of instruction and, usually, in the Himalayas, if people are really serious about Buddhism, they want to become ordain. In Bangladesh, the schools are for little girls among the Buddhist people living near the border with Myanmar. There are a lot of Buddhist people living in Bangladesh as well, a one percent minority. The schools in Bangladesh have been very successful in giving opportunities to girls who otherwise would not receive any education and are also very vulnerable to trafficking. These girls in the border areas often get snatched and sold. So, if they are educated, they have more confidence and other financial opportunities, which is much better.

신미아:

![]() 현재 서양에서 전개되고 있는 불교는 전통적인 아시아 불교와 조금 다릅니다. 승단 내에서 여성의 지위도 조금 다르구요. 서양 불교의 이런 새로운 움직임이 아시아 불교내 여성의 지위에도 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 생각하시는지요?

현재 서양에서 전개되고 있는 불교는 전통적인 아시아 불교와 조금 다릅니다. 승단 내에서 여성의 지위도 조금 다르구요. 서양 불교의 이런 새로운 움직임이 아시아 불교내 여성의 지위에도 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 생각하시는지요?

The Western Buddhism that is currently developing in the West is a little different from traditional Asian Buddhism. The status of female Buddhists in the Sangha is also different. Do you think this new trend of Western Buddhism could affect the status of female Buddhists in traditional Asian Buddhism?

카르마 렉셰 쏘모스님:

![]()

우선 서양에도 다양한 불교 형태가 있다고 말씀드리고 싶습니다. 이 질문에 맞게 대답하기 위해 서양내 다양한 불교 전통을 좀 살펴보겠습니다. 먼저, 위빠사나 불교는 재가자가 주축을 이루는 데 위빠사나 명상에 초점을 둡니다. 여성과 남성 모두에게 평등하게 열려있으며 여성 법사들도 있습니다. 서양에는 선불교 전통도 있지요. 선불교는 북미와 유럽에서 정말 인기가 있으며, 명상을 중시합니다. 선불교에서도 많은 여성 재가자 및 출가 수행자들이 스승으로 인정받고 있습니다.

티베트 불교 역시 아주 인기입니다. 티베트 불교에서 대다수 스승들은 아시아 남성들입니다. 다른 불교 전통들과는 조금 다르지요. 물론 스승으로 인정받는 여성들도 있습니다. 빼마 최된, 텐진 빠모, 툽텐 최된 스님 같은 분들이지요. 하지만 대다수는 아시아 남성들이며, 비구 스님들입니다. 남성 재가자도 약간 있긴 합니다. 티베트 절에 가보면 종종 주지는 남성이고, 일하는 사람들은 대부분 여성인 경우를 자주 봅니다.

그 밖에 정토진종도 있습니다. 사실 미국의 초기 불자들은 중국인과 일본인들이었습니다. 그들 중 다수는 정토진종 신자였습니다. 북미 대륙에 약 이십오만 명 정도 있는 데, 주로 일본계 미국인 사회내에서만 성행하는 경향이 있습니다. 정토진종 역시 여성에게 문호를 열기 시작했고, 지난 삼사십 년 동안 여성들도 출가하여 계를 받을 수 있게 되었습니다. 여성들이 점점 지도적 역할을 맡고 있다고 합니다. 대단히 큰 변화라고 할 수 있지요.

그리고 태국 불교, 한국 불교, 라오스 불교, 캄보디아 불교, 미얀마 불교 등 다른 불교 전통들도 서양에 들어왔습니다. 미국의 모든 대도시에는 불교사찰이 있지요. 특히, 베트남 공동체의 규모가 큰 데, 보통 도시마다 베트남 사찰이 네다섯 곳 정도 됩니다. 그리고 여성들이 실질적으로 사찰을 이끌어가는 경우가 많습니다. 인원 면에서도 베트남 비구니 스님들이 비구 스님들보다 더 많습니다. 여성 지도자들이 점점 더 눈에 띄고 있구요.

또다른 흐름도 있습니다. 세속불교(Secular Buddhism)입니다. 사람들이 업이나 윤회같은 것을 믿지 않고, 부처님께 절을 하지 않으면서도 불교를 통해 정신수양을 할 수 있다는 생각입니다. 요즘 인기를 끌고 있는데, 아마도 기독교나 유대교에 만족하지 못하는 사람들이 있기 때문인 것 같습니다. 또, 많은 사람들이 보통 12년 간 과학 교육을 받다 보니, 불교를 다른 방식으로 이해하려고 합니다.

북미 불교의 다른 점은 여성 지도자가 상당히 많다는 것입니다. 계속 늘어나고 있구요. 하지만 저는 아시아 여성 불자들의 지위가 향상된 것이 꼭 서양 여성들 때문이라고는 생각하지 않습니다. 아시아에서 많은 일들이 일어나고 있기 때문이지요. 예를 들어, 아시아 여성들은 지난 50년 간 남성들과 거의 같은 수준으로 교육을 받아왔습니다. 물론 모든 아시아 나라들이 그런 것은 아닙니다만 한국이나 몽골, 일본, 대만, 베트남 같은 곳에서 여성들은 점점 더 남성들과 거의 동등하게 세속 교육을 받을 수 있습니다.

종교 분야에서도 더 많은 여성 지도자들을 발견할 수 있습니다. 이런 것이 서구의 영향이라고는 말할 수 없어요. 이따금씩 서양 여성들은 아시아 불교에 영향을 미쳤다고 칭송을 받기도 하고, 비난을 받기도 합니다. 하지만 저는 잘 확신이 서지 않네요. 이미 1920년와 1930년대에서도 아시아에서 페미니즘을 찾아볼 수 있거든요. 그때 당시의 한국과 일본에는 페미니스트들이 있었습니다. 분명 서양 여성 불자들 때문에 그런 것은 아니지요. 다른 원인이 있었습니다.

제가 자신있게 말씀드릴 수 있는 것은 샤캬디타 안에서 우리는 그동안 참으로 생산적으로 서로 배우고 경험을 나누며 문화를 교류했다는 점입니다. 서로 동등한 위치에서 서로가 서로에게 배운 거지요. 우리는 다 그러니까요. 어떤 우열이 있는 것이 아닙니다. 서양 여성들은 한국과 베트남 여성 불자들의 헌신을 보면서 큰 힘을 받습니다. 영향을 받는 거지요.

First of all, Buddhism in the West has taken many different forms, so to answer this question properly, we need to recognize the diversity of Buddhist traditions currently in the West. We have, for example, the Vipassana Buddhist tradition, which is mostly a laypeople’s tradition focused mostly on Vipassana meditation. It’s open to men and women equally, and some of the teachers are also women. We also have the Zen tradition. Zen Buddhism is really popular in North America and Europe, and it is also very much focused on meditation. In that tradition also, we find a lot of women teachers, both nuns and laywomen who are recognized teachers.

Then, we have the Tibetan tradition, which is also very popular. In the Tibetan tradition, most of the teachers are Asian males, so that has been a bit different. Certain women have emerged as teachers; for example, Pema Chodron, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, and Thubten Chodron are recognized teachers, but the vast majority are still Asian male teachers. That dynamic is a bit different, and most of those males are monks, but some are also laymen. In those centers, we often find that the leader is male, and the workers are mostly women.

We also have the Jodo Shinshu tradition. The earliest Buddhists in the United States were actually the Chinese and Japanese, and the largest group among them is Jodo Shinshu, which is Pureland tradition. It has about a quarter of a million followers in North America, making it largest group, and, yet, it has very little representation. It tends to be rather concentrated among the Japanese-American community. However, they are also starting to open up and women have been getting ordained in that tradition for the last 30 or 40 years. I’ve noticed, being from Hawaii, women are taking more leadership positions in that tradition – quite a major change I would say.

Now, we also Thai, Korean, Lao, Cambodian, Burmese Buddhism among many other traditions. Every major American city has a Buddhist temple. The Vietnamese community is very large, and in most cities, there are four or five Vietnamese temples, and many of these temples are led by women. In fact, Vietnamese nuns tend to outnumber the monks. So, we see women are more and more visible, not only in the kitchens, but also as leaders.

There are also other trends. One popular trend is secular Buddhism, which means that we can practice mental development without believing in karma, without bowing to the Buddha, without believing in rebirth, these kinds of things. This is also becoming a popular trend perhaps because some people didn’t feel satisfied with Christianity or Judaism. Also, many people have had 12 years of scientific education, so they come to understand Buddhism in a different way.

What’s different about North American Buddhism is the large participation of women in leadership roles; although still not 100 percent, it’s improving. However, I don’t think that the improved status of Asian women in Buddhism is necessarily due to Western women. This is because there are other things going on in Asia. For example, women in Asia in the last 50 years have been getting education on a par with men. This, of course, is not true to all Asian societies, but in countries like Korea, Mongolia, Japan, Taiwan, and Vietnam, women are getting the same secular educational opportunities as men. In the field of religion also, we find that women are taking leadership positions in the temples. We cannot necessarily say that that’s a Western influence. Sometimes Western women are getting credited or blamed for influencing Asian Buddhism. Yet, I’m not sure of this because feminism has been going on in Asia for decades. Back to the 1920s and 30s there were Korean and Japanese feminists, and it certainly was not not the influence of Western Buddhist women; it was other influences.

What I can say with confidence is that in the Sakyadhita International Buddhist Women movement, there has been a really productive cultural exchange, an exchange of learning and experiences that, I think, has been equal on both sides – we’re all learning from each other; it’s not a hierarchical relationship. Western women see the devotion of the Korean and Vietnamese women and become very inspired. So, Western women are becoming influenced just as much by Asian women as Asian women are being influenced by Western women. I think it goes both ways.

신미아:

![]() 지금 세상은 빠르게 변하면서 하나로 통합되고 있습니다. 한국은 그 중에서도 특히 급격한 변화를 겪고 있습니다. 이러한 사회 변화 속에서 문제도 많이 나타나는 데요, 스님께서는 불교가 현대 사회의 문제를 해결하는 데 어떻게 기여할 수 있다고 생각하시는지요?

지금 세상은 빠르게 변하면서 하나로 통합되고 있습니다. 한국은 그 중에서도 특히 급격한 변화를 겪고 있습니다. 이러한 사회 변화 속에서 문제도 많이 나타나는 데요, 스님께서는 불교가 현대 사회의 문제를 해결하는 데 어떻게 기여할 수 있다고 생각하시는지요?

The world is now integrating into one and changing rapidly. In particular, Korea is one of the fastest changing countries in the world. In this rapid transition, various problems are emerging. What do you think is the way Buddhism can contribute to society in this modern era?

카르마 렉셰 쏘모스님:

![]()

저는 불교가 다양한 방법으로 기여할 수 있다고 생각합니다. 서양 사회는 좋은 쪽과 나쁜 쪽 양쪽 방향으로 변하고 있습니다. 환경 위기는 서양물질문명이 범인이라고 할 수 있지요. 경제적 불평등과 부의 격차 역시 서양이 주도하고 있지요. 큰 문제입니다. 국제기업형 자본주의 역시 아시아 사회에 안좋은 영향을 미치고 있습니다. 아마 아시아에서는 서양처럼 소득격차가 크지 않을 것입니다. 표준적인 일본 회사의 경우, 최고경영자는 노동자 평균 소득의 약 스무 배를 법니다. 하지만 미국에서는 육백 배 정도 됩니다. 동서양의 문제인지는 모르겠지만 사회관계망 미디어나 휴대전화 같은 것들도 모든 현대인들에게 영향을 미칩니다. 무언가에 집착하는 것 역시 꼭 동서양의 문제는 아닙니다.

어쨌든 불교는 이런 문제들을 해결하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있습니다. 불교는 우리가 어떻게 마음을 가라앉히고 분노와 욕망에 잘 대응하면서 다른 사람과 조화롭게 살 수 있는 지 가르쳐줍니다. 현대인들은 영적인 깊이를 잃어버리고, 소외되고, 우울해 하며, 어떨 때에는 자살을 시도하기도 하고, 무언가에 중독되기도 합니다. 불교에는 오래된 마음수양 전통이 있습니다. 자신의 마음을 잘 닦으면 외부 세계에 의존하지 않고 스스로 행복해질 수 있다는 것입니다. 이것은 이기적인 것이 아닙니다. 우리는 각자 자신의 행복을 책임져야 한다는 이야기이지요. 어떻게 해야 행복할 수 있는지 배워서 우리 가족 안에서, 그리고 공동체 안에서 행복을 만들어낼 수 있습니다. 그래서 불교가 여러 방면에서 아주 도움이 된다고 생각합니다.

특히, 어떻게 마음을 닦고 서로 더 바람직하며 행복한 관계를 만들 수 있는 지 알려주니까요. 우리가 더 이상 쇼핑같은 것에 집착하지 않으면 더 건강한 생활방식을 만드는 데 훨씬 더 많은 에너지를 창의적이고 자유롭게 사용할 수 있을 것입니다.

I think there are many ways that Buddhism can contribute. For sure, Western society is changing in both positive and negative ways. If we look at the environmental crisis, I think we can credit Western material culture as the culprit. Also, with economic injustices and the disparity of wealth, the West is also taking a leadership role. This is problematic and, often with global corporate capitalism, we find that international corporate capitalism affects Asian societies in a very negative way. Maybe the disparity is not as great in Asia as in the West. For example, in a standard Japanese company, the CEO makes twenty times the income that the average worker makes. However, in the United States, it’s something like 600 times as much as the average worker. Things like cellphone use, addition to social media – I don’t know if it is an East-West thing, but it is definitely an issue of modernity that impacts us all. Addiction to substances of all kinds is also not necessarily an East-West problem, but it is something that Buddhism can help us address by teaching us how to calm our minds and deal with anger and desire, how to live in harmony with each other, and how to develop communities that are peaceful and have a spiritual root. Modern people are getting separated from their spiritual depth and then they become alienated, depressed, unhappy, sometimes suicidal, and addicted to substance abuse.

Buddhism can help because Buddhism has an ancient culture of developing our minds so that we can be happy without depending on anything outside of ourselves. This is not in a selfish, but in the sense that we are responsible for our own happiness. Therefore, by learning how to do that, we can also create happiness in our families and in our communities. So, I think Buddhism can be helpful in so many ways, especially in how to train the mind and create better and happier interrelationships with each other. Mindful listening skills, for instance, are something we can use in our families and in our relationships, in our workplace, and in our temples.

Basically, Buddhism can teach us how to be calm and how to be creative. When we are no longer obsessed with, say, shopping, we can free up a lot of energy that can be used for creative endeavors to create a healthy lifestyle.

신미아:

![]() 마지막으로 한국의 샤카디타 미래 세대와 불교계에도 한 말씀 부탁드립니다.

마지막으로 한국의 샤카디타 미래 세대와 불교계에도 한 말씀 부탁드립니다.

Could you share some final words with the Korean Buddhist societies and the future generations of Sakyadhita?

카르마 렉셰 쏘모스님:

![]()

한국 여성불교인들이 세대를 넘어 조화롭게 서로 함께 일했으면 합니다. 제가 보기에 한국에는 세대 차이가 있는 것 같아요. 한국은 지난 100년 간 수많은 변화를 겪었습니다. 저는 이것을 배움의 기회로 여겼으면 합니다. 기성 세대의 경우 여성들은 복종하는 것이 당연시되었을 겁니다. 비록 싫어도 말이지요. 지금 젊은 세대들은 이러한 기성세대의 어려움을 이해하고, 그들의 지혜를 배우고, 또 어떻게 인내해왔는지 알았으면 합니다. 동시에 긍정적인 변화를 이끌어내야지요. 모든 이의 이익을 위해 자비와 자애, 지혜로서 세대간 변화를 이끌어내기를 바랍니다. 이것은 나머지 세계에도 선물입니다.

끝으로, 한국 불교 문화에 감사와 존경을 보냅니다. 한국은 정말 특별한 전통을 가지고 있습니다. “아시아에서 가장 잘 보존된 비밀”이라고도 하지요. 바로 아름다운 사찰들과 유구한 불교 전통입니다. 식민지배를 받던 시절도 있었지만 이 귀중한 전통을 지켜냈고, 이것은 다른 나라들에게도 선물입니다. 저는 한국 불교인들이 전통에 자부심을 느끼고 지지해주기를 바랍니다. 그리고 이 전통이 한국과 전 세계 중생들의 행복을 위해 널리 번창하기를 바랍니다.

I hope that Buddhist women in Korea will be harmonious and work together across generations. I see, in Korea, you have generational differences. Korea has gone through so many changes in the last 100 years, but I think we can see this as a learning opportunity. Let Buddhist women take the lead in understanding how to meet these challenges. In the older generation, women may have accepted subordination as normal, even if they didn’t like it. However, now, the younger generation can also appreciate the difficulties of the older generation and learn from their wisdom and how they practiced patience in certain situations; and, at the same time, help to inspire positive changes. This is something that could also be a gift to the world – how to tackle a difficult issue of cross-generational change with compassion and loving kindness and wisdom to everyone’s benefit. In this way, everyone gains from learning how to be patient and how to address these changes using Buddhist principles.

I would like to express my admiration and appreciation for Korean Buddhist culture. I think you have something very special in Korea, sometimes called “Asia’s best kept secret” with the beautiful monasteries and ancient traditions. It is so close historically that you can easily recover your traditions. There was a period of colonialism, but you’ve managed to preserve this priceless Buddhist heritage that is a gift to the world. So, I would like to encourage Korean Buddhists to be proud of your traditions and to support them, and I hope they will flourish for the happiness of all beings in Korea and throughout the world.

본 인터뷰는 제16차 샤카디타 세계불교여성대회가 열린 블루마운틴 페어몬트 리조트에서 진행되었다. 대회에 참가하지 못한 시드니 기자를 대신하여 인터뷰를 진행해준 신미아 님의 수고에 감사드린다.

*시드니 톰슨은 샤카디타 코리아 홍보간사를 맡고 있으며, 샤카디타 코리아 뉴스레터 영문판 에디터로 일하고 있습니다.

*시드니 톰슨은 샤카디타 코리아 홍보간사를 맡고 있으며, 샤카디타 코리아 뉴스레터 영문판 에디터로 일하고 있습니다.

*Sydney Thompson is Sakyadhita Korea’s publicity assistant and writer for Sakyadhita Korea’s English content.