[시드니와 함께하는 세계 속 붓다의 딸, 4탄]

인터뷰: 샤카디타 인터네셔널 에일린 스님 Interview with Ven. Aileen

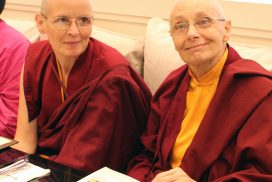

에일린 베리 스님은 제쭌마 텐진 빠모 스님의 시자스님이며, 돈규 가찰 링 사원에서 활동하고 있다.

*기자: 시드니 톰슨, *번역: 신미아

시드니 Sydney:

![]()

먼저 스님 소개를 부탁드립니다. 성함과 출신 국가,어떻게 처음 불교를 알게 되셨거나 접하게 되셨는지요.

Could you please introduce yourself (your name, country, and how you first learned about Buddhism or came into contact with Buddhism).

에일린 스님 Ven. Aileen:

![]() 저의 서양식 이름은 에일린 베리(Aileen Barry)입니다. 저는 아일랜드에서 태어났습니다. 재미있는 것은 저의 삼촌 두 분은 천주교 신부이시고, 대고모 한 분은 수녀이시라는 점이지요. 저는 아일랜드 계 천주교 가정에서 자랐습니다. 심지어 저의 숙모께서는 제가 여성 출가 수행자가 되기를 기도하셨습니다. 하지만, 어느 종교인지는 말씀하지 않으셨지요!

저의 서양식 이름은 에일린 베리(Aileen Barry)입니다. 저는 아일랜드에서 태어났습니다. 재미있는 것은 저의 삼촌 두 분은 천주교 신부이시고, 대고모 한 분은 수녀이시라는 점이지요. 저는 아일랜드 계 천주교 가정에서 자랐습니다. 심지어 저의 숙모께서는 제가 여성 출가 수행자가 되기를 기도하셨습니다. 하지만, 어느 종교인지는 말씀하지 않으셨지요!

제가 처음으로 불교와 마주하게 된 것은 20대 후반 무렵입니다. 제가 런던에 살고 있을 때였습니다. 천주교 신부이신 제 삼촌 한 분이 바티칸에서 집으로 돌아가는 길에 저를 보러 런던에 오셨습니다. 저는 삼촌을 근처에 있는 미술관에 모시고 갔는데, 마침 거기에서 티베트 불교 전시회가 열리고 있었습니다. 저에게 삼촌을 그 곳으로 모시고 가는 것이 무언가 아주 자연스럽게 느껴졌습니다. 삼촌을 도발하거나, 삼촌에게 불교를 강요할 의도는 전혀 없었지요.

여하튼 그 전시회에서 저는 일군의 스님들을 보았습니다. 즉시 저는 스님들에게 아주 강한 유대감을 느꼈습니다. 스님들은 제가 가능하리라고 생각했던 그 이상의 인간처럼 느껴졌지요. 스님들은 자기 자신으로부터 자유로워 보였습니다. 스님들에게는 술을 마시는 것과 같이 무언가를 더 해야만 편해질 수 있는 그런 긴장감이 없는 것 같았습니다. 오히려 스님들은 무언가를 포기하셨지요. 저는 그분들이 무엇인가로부터 자유로운 모습에 가장 크게 영향을 받았습니다. 저는 그 분들이 무엇에서 자유로운지, 어떻게 그 경지를 이루었는지 몹시 궁금해졌습니다.

그 후 저는 호주에 머물게 되었는데, 호주로 가는 길에 인도에 들르고 싶었습니다. 런던의 전시회에서 스님들과 접촉하면서 저는 히말라야와 다람살라도 방문해서 불교에 대해 더 알아보고 싶었습니다. 그리고 다람살라에 있는 어느 센터에서 불교와 명상법에 대한 아주 훌륭한 입문 과정을 마쳤습니다. 그 과정에서 제가 정말 충격을 받은 것은 이것을 가르치는 선생님들이었습니다. 선생님들께서는 어떤 자질을 갖고 계셨는데, 저에게 이런 생각이 들게 했지요.“선생님들이 가지고 있는 것이 무엇이건 간에 나도 그걸 갖고 싶어.”

시드니:

![]()

서양인이면서 티베트 비구니 스님으로 생활하시는 것이 어떠신지요?

As a Westerner, how is your life as a Tibetan Buddhist nun?

에일린 스님:

![]() 티베트 불교 체계에서 계를 받은 여성들을 위한 공동체는 세계적으로도 거의 없습니다. 게다가 우리는 아직도 매우 전통적인 수련 방식을 갖고 있는 체계 속으로 들어갑니다.

티베트 불교 체계에서 계를 받은 여성들을 위한 공동체는 세계적으로도 거의 없습니다. 게다가 우리는 아직도 매우 전통적인 수련 방식을 갖고 있는 체계 속으로 들어갑니다.

티베트에서 비롯된 이 방식은 주로 아주 어린 나이 때부터 수련을 시작하는 데 초점이 맞춰져 있습니다. 어린 사미와 사미니들이 핵심적 가르침들을 모두 외우게 하는 것으로 수련을 시작하지요. 이들이 가르침을 모두 외우고 나면 다시 그 가르침들을 분해해서 공부하고 소화합니다. 서양인에게, 그리고 일반적인 성인에게는 거의 불가능한 일이죠. 그래서 그 체계 안으로 쉽게 들어갈 수 없습니다. 문화적 차이도 크지요. 티베트 언어에 통달해야 합니다. 몇몇 서양인들이 전통적인 티베트 불교 수도 공동체에 들어갔지만, 오직 소수만이 살아남아 잘 활동할 수 있습니다. 여러분이 그렇게 할 수 있더라도 그것은 아주 예외적인 일입니다.

또 다른 어려움은 티베트 불교가 티베트 바깥으로 나올 때, 난민의 지위에 있었고, 인도에서 완전히 재건해야 했다는 점입니다. 티베트 불교가 온 세계에 널리 퍼지면서 스승님들은 비구 사원과 비구니 사원을 모두 재건하고, 여기에 필요한 예산도 끌어오는 중요한 역할을 맡게 되었습니다. 그래서 티베트 불교가 점차 국제화되고 있지만, 언제나 초점은 멀리 인도에 있는 티베트 사람들이었습니다. 그 결과 우리는’진짜 수도자’와 대비되는 외부인이라고 느끼게 되었습니다. 도움이 필요하면 다른 방식으로 스스로 후원 네트워크를 찾아야 하지요. 어떤 때에는 그들과 우리 서양 여성 비구니 사이에 투명한 막이 한 겹 있는 것 같습니다. 우리를 “진짜 수도자들”이라고 생각하지도, 티베트 불교 계맥을 잇고 있다고 여기지도 않는 것 같아요. 또 우리가 여성이기 때문이지요.

우리를 다르게 인식하기 때문에 종종 우리, ‘외부인’들이 티베트 수도 사원들을 후원해주기를 기대합니다. 티베트인들이 아직도 난민 처지인지라 금전적으로나 다른 형태로도 도움을 받기 어렵기 때문이지요.

시드니:

![]()

현재 생활하고 계시는 돈규 가찰 링 사원에 대해 소개해주세요.

Tell me about Dongyu Gatsal Ling Nunnery.

에일린 스님:

![]() 제쭌마(텐진 빠모 스님)께서는 2000년도에 스승님의 요청에 따라 여성 출가자를 위한 사원을 건립하기 시작하셨습니다. 빠모 스님의 스승께서는 인도에 그 분의 법맥을 잇는 비구니 사원을 짓고자 하셨습니다. 그때까지 한 곳도 없었거든요. 이제 사원은 완공되었고, 100명이 좀 넘는 여성 출가자들이 있습니다. 그 중 여덟 분은 장기 안거 중이십니다. 똑덴마 (Togdenma) 종파에 속하거든요. 돈규 가찰 링 비구니 사원은 장기 안거 수행법을 포함해 토그덴마 종파를 재건했습니다. 장기 안거 중이신 분들은 근처 사찰에 있는 똑덴(Togden)의 지도를 받습니다. 그래서 이 사찰과 돈규 가찰 링 사이에는 사이 좋은 오누이 관계가 형성되어 있습니다.

제쭌마(텐진 빠모 스님)께서는 2000년도에 스승님의 요청에 따라 여성 출가자를 위한 사원을 건립하기 시작하셨습니다. 빠모 스님의 스승께서는 인도에 그 분의 법맥을 잇는 비구니 사원을 짓고자 하셨습니다. 그때까지 한 곳도 없었거든요. 이제 사원은 완공되었고, 100명이 좀 넘는 여성 출가자들이 있습니다. 그 중 여덟 분은 장기 안거 중이십니다. 똑덴마 (Togdenma) 종파에 속하거든요. 돈규 가찰 링 비구니 사원은 장기 안거 수행법을 포함해 토그덴마 종파를 재건했습니다. 장기 안거 중이신 분들은 근처 사찰에 있는 똑덴(Togden)의 지도를 받습니다. 그래서 이 사찰과 돈규 가찰 링 사이에는 사이 좋은 오누이 관계가 형성되어 있습니다.

여성 수행자 몇 분은 수련을 마치고 지금은 선생님이 되었습니다. 사원에는 어린 소녀도 꽤 있는데, 몇 명은 겨우 7~8세에 불과합니다.

어린 소녀들을 위한 수련 일정은 따로 있습니다. 읽기, 쓰기, 산수, 과학 같은 기초교육에 좀 더 집중하지요.

전통적으로 티베트 불교를 학구적인 쪽과 제례 의식에 집중하는 쪽 두 범주로 나누는 경향이 있습니다. 명상은 수행시설에서 자주 시행하는 방법은 아닙니다. 그렇지만 오래된 전통 티베트 불교 경전에는 이렇게 적혀있습니다. “공부하라, 사색하라, 명상하라.”

시간이 지나면서 명상 수행의 과학적이고 지적인 관점을 강조하는 경향이 널리 퍼졌습니다. 독특하게도 제쭌마께서는 지적인 면과 제례의식, 명상 수행 세 가지를 좀 더 균형 있게 이해하려고 하십니다. 그래서 우리 사원에서는 ‘종합 꾸러미(complete package)’를 제공하지요. 비구니들은 자신이 가장 중점적으로 수행할 방식을 선택하기 전에 모든 방법을 맛볼 수 있습니다. 학문, 명상, 사색 외에도 비구니들은 부엌일이나, 성물 공예 같은 사원 생활의 여러 가지 다른 측면을 경험할 수도 있습니다.

사실, 우리 사원의 비구니 한 분은 상당한 의료 훈련을 받았고, 비구니 두 분은 사원의 손님용 숙소를 관리하고 계십니다. 여성 재가자나 출가하신 방문자를 위한 단기 안거 과정도 있는 데, 비구니 몇 분이 지도하시지요. 외부에서 오는 묵상 수도자들은 따로 지도를 하지 않기 때문에 반드시 자신만의 수행 법을 갖고 있어야 합니다.

시드니:

![]()

어떻게 텐진 빠모 스님의 시자스님이 되셨는지요? 빠모 스님께는 무엇을 배우셨는지, 저희에게 꼭 이야기 해주고 싶은 일화가 있으신지요?

How did you Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, and as her assistant, what did you learn from her and/or what is the best anecdote you can give us?

에일린 스님:

![]() 저는 2000년경 호주에서 빠모 스님을 만났습니다. 스님께서 제가 일하고 있던 감옥에 오셨지요. 감옥에 방문객을 데려오는 것은 아주 어려운 일이며 수차례 경찰의 검문을 받아야 합니다. 그런데 빠모 스님께서는 경찰 검문을 통과하지 못했고, 경찰은 스님을 구금했습니다. 아주 드문 일이었지요. 스님께서 꼭 그 곳에 있어야 했기 때문이라고 제가 생각하던 것이 기억납니다.

저는 2000년경 호주에서 빠모 스님을 만났습니다. 스님께서 제가 일하고 있던 감옥에 오셨지요. 감옥에 방문객을 데려오는 것은 아주 어려운 일이며 수차례 경찰의 검문을 받아야 합니다. 그런데 빠모 스님께서는 경찰 검문을 통과하지 못했고, 경찰은 스님을 구금했습니다. 아주 드문 일이었지요. 스님께서 꼭 그 곳에 있어야 했기 때문이라고 제가 생각하던 것이 기억납니다.

감옥에서 일할 때, 정신 병동에서 온 여성 한 분이 있었습니다. 저는 그 여성에게 특별한 관심을 갖고 있었습니다. 그 분의 남편이 불교신자였거든요.

그녀는 과거에 약을 먹고 자살을 시도한 적이 있었습니다. 불행히도 그녀는 자식들에게도 약을 먹였고, 아이들은 사망했습니다. 여하튼 저는 그녀와 일하는 것이 녹록치 않았습니다. 하지만 그녀가 계속 저를 만나게 해달라고 요청했기 때문에 그녀를 쭉 면담했습니다. 어느 날, 저는 빠모 스님과 함께 그녀를 만나러 갔습니다. 교도관은 처음에는 우리를 들여보내기 꺼려했지요. 출입허가를 기다리는 동안 빠모 스님께서는 아주 조용히 얌전하게 서 있었습니다.

마침내 허가가 떨어지자 스님은 마치 어머니가 너무나 끔찍한 일을 겪은 자식을 마침내 다시 만나듯이 그 여성에게 달려갔습니다. 그녀는 스님을 팔로 껴안고, 아주 아주 오랫동안 엉엉 울었지요. 이것은 제가 빠모 스님과 함께 지내기 시작하던 초반 무렵 있었던 일입니다. 스님께서 고통에 찬 이 여인을 어떻게 사랑하고 대하시는지 저라면 할 수 없었던 그 일을 지켜보면서, 제가 어떻게 고통을 겪고 있는 사람들을 도와야 할지 알 수 있었습니다.

제가 스님의 시자가 된 것은 제가 호주에 살고 있을 때였습니다. 당시 스님께서 비구니 사원을 건립하도록 돕고 있는 여성들을 몇 분 알게 되었지요. 이 분들은 스님께서 시자를 구하는 것을 알고 있었습니다. 그 분들이 저에게 혹시 스님의 시자가 되고 싶은 지 물어 보셨을 때, 저는 펄쩍 뛰면서 도저히 그 일을 할 수 없다고 생각했습니다. 그런데 스님께서 저에게 이메일을 보내셔서 더 빨리 메일을 보내지 못해 미안하다고 말씀하셨습니다. 스님께서 컴퓨터에 커피를 쏟았었다고 하셨지요. 저는 불현듯 이런 생각이 들었습니다. “내가 시자가 되어도 괜찮겠다. 스님께서 컴퓨터에 커피를 쏟으셨다니 말이야. 그 분도 실수를 하시는 구나. 그렇다면 나도 그 분과 함께 할 수 있을 거야.” 그것이 시자가 되는 데 동의한 이유입니다.

이제 제가 스님과 함께 일한 지 7년이 되어갑니다. 우리는 아주 많은 곳을 여행합니다. 제 기억에 작년(2018년)에는 열 여덟 개 나라를 다녀왔지요. 온 세계 다양한 문화에 속한 사람들을 만나고, 스님께서는 또 여러 가지 상황에서 법문을 하시기 때문에 세계 많은 사람들이 처한 조건을 이해하는 데 정말 도움이 됩니다. 비록 외적인 양상은 서로 다른 것처럼 보여도 그 밑바탕을 보면 우리는 모두 같고, 인류라는 한 가족입니다.

제가 스님과 함께 여행하고 일하면서 한 가지 더 배운 것은 성찰하고 질문하는 것입니다.

“얼마나 많이 내 마음을 닦고 있지? 나는 더 나은 인간이 되어가고 있는가?”

이 질문은 좋은 불교도가 되는 것에 대해 묻는 것은 아닙니다. 좋은 사람이 되는 것에 대한 이야기이지요. 만약 여러분이 불교신자라는 것을 여러분의 정체성 가운데 가장 중요한 요소로 생각하신다면, 여러분은 가장 중요한 것은 여러분이 인간이라는 점, 그 무엇보다도 중생의 하나라는 점을 생각하지 못하고 있는 것입니다.

시드니:

![]()

불교 전반에 대해서, 그리고 특별히 샤카디타에 대한 장래 희망이나 바람이 있으신지요?

What are your future hopes and wishes for Sakyadhita in particular and for Buddhism in general?

에일린 스님:

![]()

저희는 샤카디타가 비종파적일 뿐만 아니라 특정 성별을 위한 단체를 넘어서서 발전하기를 희망합니다. 남자와 여자 양쪽 모두에게서 지지를 받을 가치가 있습니다. 우리 모두는 여기에 함께 합니다. 샤카디타도 모든 이를 포용한다면 이상적일 것입니다.

우리 대부분이 흔히 저지르는 실수는 “누구를 비난할 것인가?”하고 묻는 것입니다. 여러 사례에서 여성들은 불공정하거나 불평등한 환경에 대해 어쩔 수 없이 남성들을 비난할 것입니다. 그렇지만 남성들을 비난하는 여성들은 오직 다른 형태의 집단적 지배와 배제를 초래할 뿐입니다. 우리가 누군가를 비난하는 것을 넘어서 함께 자비로운 삶을 영위해 나간다면 아주 멋질 것입니다.

샤카디타가 적극적으로 성평등을 촉진하는 비종파적 단체가 되는 것이 저의 가장 큰 희망입니다.

일반적인 불교에 대한 바람을 이야기하자면, 아마도 규범을 따를 필요가 없다는 점이 될 것입니다. 부처님께서 처음 궁전을 나섰을 때 네 가지 고통의 표상을 보셨습니다. 그 가운데 네 번째는 사문이었지요. 부처님께서 사문을 보지 못하셨다면 깨달음의 길로 나설 수 있다는 것을 모르셨을 겁니다. 그러므로 저에게 불교의 핵심은 이 세계에서 규범을 벗어나 출가해서 ‘직업정신이 투철한 전일제 과학자”(full-time professionally-minded scientists’ 가 되려고 노력하는 사람들의 사례를 만드는 것입니다.

자기 자신의 길을 따르는 이른 바 ‘과학자’란 사원의 수행자만을 말하는 것은 아닙니다. 제가 앞으로도 계속되었으면 하는 불교의 모습은 공동체를 위해 봉사하고, 함께 참여하는 불교입니다. 제가 로쉬 조안 할리팩스 (Roshi Joan Halifax)씨가 운영하는 뉴멕시코의 일본 선 센터에서 안거를 하고 있을 때, 저는 다른 사람을 섬기고 노숙자들이 진실로 존경받을 만한 사람이 되도록 돕는 그 분의 ‘참여 불교’를 발견했습니다. 불교는 마치 국경 없는 의사회처럼 되어야 합니다. 우리는 불교신자만 보살피지 말고 모든 사람에게 자비와 봉사를 베풀어야 하지요. 끝으로 우리는 다른 종교를 가진 사람들과 접촉하고 그 분들의 종교로부터 배울 수 있도록 할 수 있는 모든 일을 다 해야 합니다.

시드니:

![]()

끝으로 저희와 나누고 싶으신 다른 말씀이 있으신지요? 어떤 말씀을 해주셔도 괜찮습니다.

Is there anything else you would like to share with us? You can tell us anything you want!

에일린 스님:

![]()

제가 강조하고 싶은 것이 있습니다. 저는 부처님까지 거슬러 올라가는 믿기 어려울 만큼 훌륭한 법맥과 가르침을 이해하는 것과 시대에 발맞추어 가는 것 사이에는 미묘한 균형이 있다고 믿습니다. 지금 우리는 지구촌에 살고 있습니다. 인간으로서 서로를 연결하는 것이 그 무엇보다도 중요합니다. 자신의 믿음을 다른 사람에게 강요해서는 안되지요. 다만 우리는 할 수 있는 한 우리의 종교가 낳을 수 있는 최고의 모범이 되어야 합니다. 우리가 그렇게만 할 수 있다면, 다른 사람들이 비록 우리가 불교도인지 아닌지 모른다 하더라도 아주 멋질 거예요.

저는 가사를 입고 돌아다닙니다. 어떤 면에서 저는 늘 불교신자라고 홍보하는 셈이지요. 언젠가 제가 호주 시드니에 있을 때, 어느 아침 길을 걷다가 술에 취한 채 즐거워 보이는 남자들을 만났습니다. 그들 중 한 명이 제 가사와 생활방식에 대해 물어보더니 불쑥 “왜 그렇게 사시나요?”하고 묻더군요. 저는 그 순간 괜히 그 길로 갔다고 후회했습니다. 하지만 그 순간 그 남자는 두 손을 모으고 절을 했습니다. 얼굴에 사랑을 가득 담고 “우리 모두를 대신해 말하고 싶습니다. 고맙습니다.”하더군요. 저는 그 남자가 고통을 벗어나는 길이 있다는 것을 인식하고 있다는 점에 대해 큰 충격을 받았습니다. 사실 우리가 해야 할 일은 그것이 전부입니다. 고통에 대한 우리의 인식과 수행법을 닦아 우리 자신의 고통으로부터 벗어나고 다른 사람들을 돕는 일 말이지요.

에일린 베리 스님(Ven. Aileen)은 제쭌마 텐진 빠모 스님의 시자스님이며, 돈규 가찰 링 사원에서 활동하고 있다.

Irish nun Ven. Aileen Barry, based at Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo’s nunnery, Dongyu Gatsal Ling, in Himal Pradesh, India.

*시드니 톰슨은 샤카디타 코리아 홍보간사를 맡고 있으며, 샤카디타 코리아 뉴스레터 영문판 에디터로 일하고 있습니다.

*시드니 톰슨은 샤카디타 코리아 홍보간사를 맡고 있으며, 샤카디타 코리아 뉴스레터 영문판 에디터로 일하고 있습니다.

*Sydney Thompson is Sakyadhita Korea’s publicity assistant and writer for Sakyadhita Korea’s English content.